Por: Ana María Zabala

Una visión del mundo lo ofrenda, la otra lo saquea y acumula.

A finales del siglo XVI, Europa se encontraba en una constante búsqueda de rutas comerciales hacia las tierras de Asia pues constantemente se oían noticias sobre la riqueza de sus cortes. Los Reyes Católicos, en un frenesí expansionista que buscó dominar toda la península ibérica, financiaron el primer viaje de Cristóbal Colón con el propósito de hallar una ruta más corta hacia Asia o “las Indias”. Al mismo tiempo, los reyes decretaban la conversión forzosa al cristianismo de los judios y musulmanes en en la península ibérica.

La embarcación de Colón se topó con las Islas Antillas, marcando el comienzo del saqueo y sufrimiento de estas tierras mal llamadas “América.”Hasta el día de hoy, nombramos a todo un continente con el nombre de un comerciante florentino por el solo hecho de notar que ésta era una tierra diferente—que no eran las “Indias.” ¿Y por qué no nombrarla con las lenguas que allí ya existían?

Colón nombró “Hispaniola,”a la isla que hoy conocemos como Haití y República Dominicana—arrebatando su nombre para apropiarse ilegítimamente de ella. Los Taínos de aquella isla les ofrecieron oro a los europeos a cambio de cuentas de vidrio, telas y otros objetos de manufactura europea. En sus cartas a los Reyes Católicos, Colón escribió sobre la posible existencia de minas de oro en esta isla. La ausencia de grandes yacimientos de oro en las Antillas frustraron la búsqueda de Colón. Sin embargo, sus relatos acerca de las riquezas de lo que llamó “las islas de las Indias,” se propagaron por Europa y sembraron los primeros cimientos del fervor que impulsó la búsqueda de El Dorado.

La fiebre del oro en lo que hoy es Colombia tomó la forma siniestra del saqueo de tumbas–la guaquería.

La fiebre del oro se inició con el avasallamiento y el saqueo de los dos imperios más grandes de Abya Yala: el Azteca y el Inca. En 1519, Hernán Cortes y su séquito hurtaron los tesoros en oro coleccionados por el emperador y los nobles aztecas. Una vez tomado y repartido el botín, establecieron minas de plata en territorio mexicano ya que este carece de grandes yacimientos de oro. En 1531, Francisco Pizarro encontró al poderoso imperio Inca, con sus templos cubiertos de lámina de oro y otras riquezas majestuosas con las que deliraban los colonizadores. Pizarro y su comitiva arrestaron al jefe inca Atahualpa. El imperio Inca pagó en oro y plata por su rescate hasta llenar un recinto de 8 mts. de largo y 6 de ancho y aún así los españoles lo asesinaron. El saqueo del Imperio Inca no tuvo igual en la historia de la colonización de Abya Yala.

En los primeros años del siglo XVI, ya existían asentamientos de colonos peninsulares en la costa Atlántica de lo que hoy conocemos como Colombia. La búsqueda del oro aquí tomó una forma particularmente macabra. Como en este territorio no se conformaron grandes imperios, sus pueblos no coleccionaban tesoros fastuosos como los incas o aztecas. De hecho, la mayoría de los tesoros ni siquiera estaban exhibidos. Generaciones de los pueblos milenarios de estas tierras enterraron oro junto con sus muertos. La fiebre del oro en lo que hoy es Colombia tomó la forma siniestra del saqueo de tumbas–la guaquería. Las tierras del Sinú fueron las primeras en ver despojados sus sepulcros sagrados. Desde allí este fenómeno perverso se expandió a todas las regiones del país con tal fuerza invasiva que la corona española promulgó una legislación especial para “la explotación de oro de tumba” y siglos después, en los 1800 la “guaquería” se convirtió en una profesión adoptada por campesinos que tenían que subsistir de alguna manera.

Con el saqueo de los Incas, Aztecas y sepulcros, surgieron historias en la península ibérica hablando de legendarios Dorados: lugares extraordinariamente ricos. Los colonizadores identificaron uno de estos Dorados con una ceremonia realizada por los muiscas en la laguna de Guatavita, en el altiplano central de Colombia:

Dijo de cierto Rey, que sin vestido, en balsas iba por una piscina a hacer oblación según él vido, ungido todo bien de trementina, y encima cantidad de oro molido, como rayo de sol resplandeciente…

Allí para hacer ofrecimientos de joyas de oro y esmeraldas finas con otras piezas de sus ornamentos… Los soldados alegres y contentos Entonces le pusieron El Dorado”.

Juan de Castellanos, 1522-1606

“…En aquella laguna de Guatavita se hacía una gran balsa de juncos, y aderezábanla lo más vistoso que podían… Desnudaban al heredero en carnes vivas y lo untaban con una tierra pegajosa, y lo espolvoreaban con oro en polvo y molido, de manera que iba todo cubierto de este metal… Hacía el indio dorado su ofrecimiento echando todo el oro y esmeraldas que llevaba a los pies en medio de la laguna, seguíanse luego los demás caciques que le acompañaban y partiendo la balsa a tierra comenzaban la música, bailes y danzas a su modo, con lo cual quedaba reconocido el nuevo electo por señor y príncipe. De esta ceremonia se tomó el nombre de El Dorado tan celebrado y que tantas vidas… ha costado”.

Juan Rodríguez Freyle, en Santa Fe de Bogotá, 1636

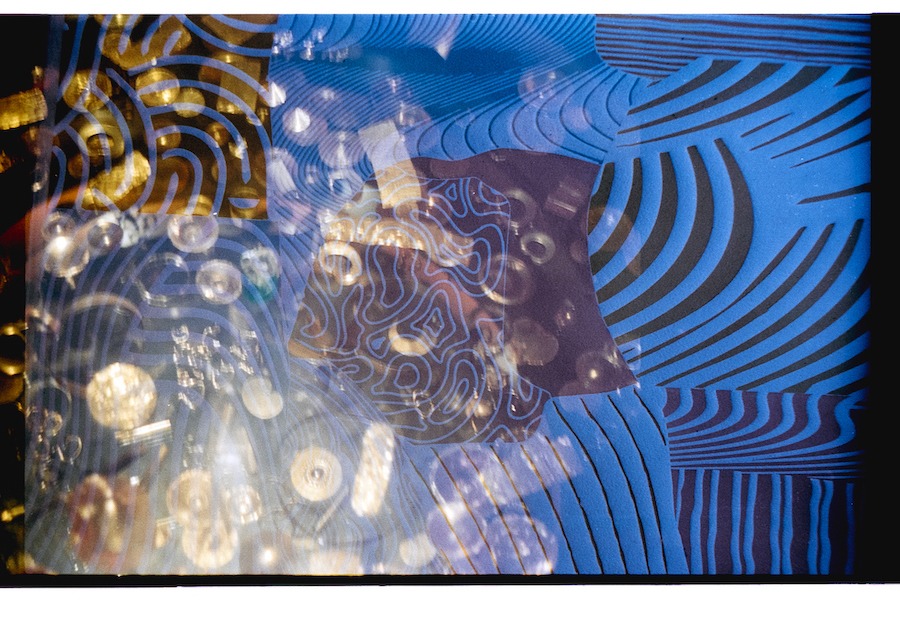

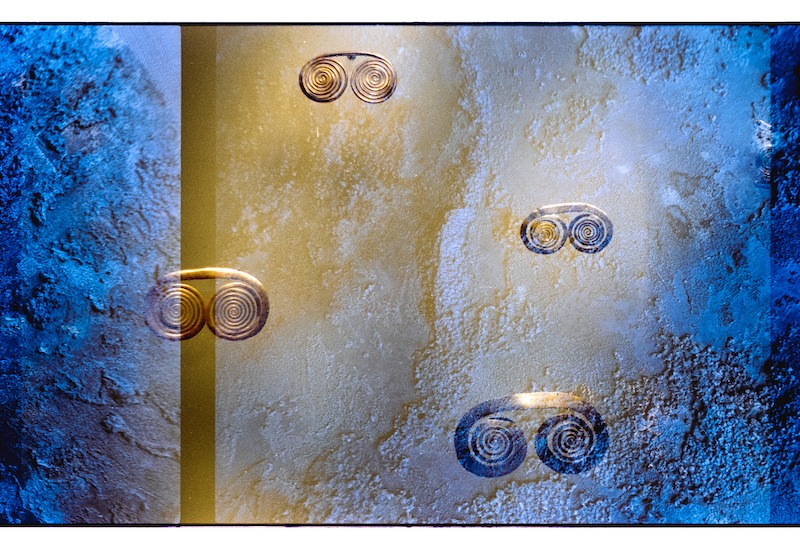

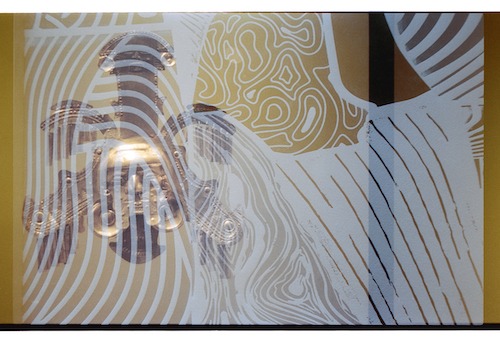

óleo y collage sobre madera con proyección de imagen de pieza orfebre”La Balsa Muisca”, expuesta en el Museo del Oro de Bogotá.

No fue en Guatavita, sin embargo, que la leyenda cobró vida, sino en en las lagunas de Siecha en el páramo de Chingaza—ese que observa al altiplano cundiboyacense desde los 2.000 y 4.100 metros de altura. Este ecosistema de alta montaña que los españoles llamaron páramo porque lo veían como una tierra empobrecida, es donde nacen la mayoría de los ríos que recorren los Andes tropicales y subtropicales y es tierra sagrada y ceremonial para los muiscas y otros pueblos.

En 1856, los hermanos Joaquín y Bernardino Tovar desaguaron parcialmente esta laguna y encontraron una figura votiva en forma de balsa que asociaron con la ceremonia de El Dorado. A esta laguna se le conoce como “la desaguada.” El cónsul alemán Salomón Koppel la vendió, legalmente en ese entonces, a un museo en Alemania, pero se destruyó en un incendio al llegar al puerto de Bremen. Más de un siglo después, en 1969, el padre Jaime Hincapié Santamaría, párroco de Pasca, Cundinamarca, recibió la visita de Cruz María Dimaté, un campesino que halló unas piezas de oro y cerámica en una cueva en el páramo que se asemejaban a la ceremonia de El Dorado. Éstas son las que se exhiben en el Museo del Oro de Bogotá y se conocen como la Balsa Muisca.

Para los pueblos indígenas en Colombia, el oro es la energía de vida del padre sol mientras que las lagunas son el vientre de la madre tierra. En el ritual que los españoles nombraron El Dorado, el cacique dorado ofrendaba oro al agua para renovar la vida en un pacto con la naturaleza.1 El pensamiento occidental redujo este mineral de gran valor espiritual a su valor monetario. Muchas de estas piezas orfebres sagradas ya no existen pues fueron saqueadas y fundidas en lingotes de oro para enviar a Europa.

El Dorado se convirtió en un espejismo delirante que impulsaría innumerables despojos y la incesante explotación de las minas de oro y plata, para las cuales los españoles secuestraron y esclavizaron a las gentes de África. Hasta el día de hoy, la gran minería y la minería ilegal de oro explota a la población del Pacífico colombiano, en su mayoría afrodescendiente e indígena. Hoy en día, Abya Yala y sus pueblos siguen siendo la mina del Norte Global—imperios que le deben su poder a las tierras que han saqueado y siguen saqueando a lo largo de siglos de colonización.

Notas

- Según el arqueólogo, Roberto Lleras Perez, el pueblo muisca dedicaba más de un 50% de sus piezas orfebres para ofrendas a la naturaleza.

Referencias

Plazas de Nieto, C., & Falchetti, A. M. (1979). La orfebrería prehispánica de Colombia. Boletín Museo Del Oro, (3), 1-53. Recuperado a partir de https://publicaciones.banrepcultural.org/index.php/bmo/article/view/7354

Vargas Martínez, Gustavo. (1934). Americo Vespucio: El Primer Nombre. Recuperado a partir de https://www.banrepcultural.org/biblioteca-virtual/credencial-historia/numero-29/americo-vespucio-500-anos-del-descubrimiento-de-america

Diosa Vargas, J., Saldarriaga Rendón, J.C. & Marín Alzate, J. A. (2016). Guaquería, la historia oculta bajo tierra. El Espectador. Recuperado a partir de https://www.elespectador.com/noticias/nacional/guaqueria-la-historia-oculta-bajo-tierra/

Banco de la República. La balsa muisca y el Dorado. Recuperado en 2021 partir de https://www.banrepcultural.org/coleccion-arqueologica/balsa-muisca

Cooper, Jago. El Dorado: The truth behind the myth, Recuperado en 2022 a partir de https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-20964114