Por: Ana María Zabala

La metalurgia floreció en una amplia región incluyendo la zona Andina de Perú, Ecuador y Colombia; Costa Rica y algunas partes de México. La tradición metalúrgica prehispánica se practicó durante 30 siglos, desde mediados del primer milenio a.C. hasta los comienzos del siglo XVI d.C., cuando se interrumpe la práctica al mismo tiempo que la colonización española erosiona el tejido de los pueblos indígenas.

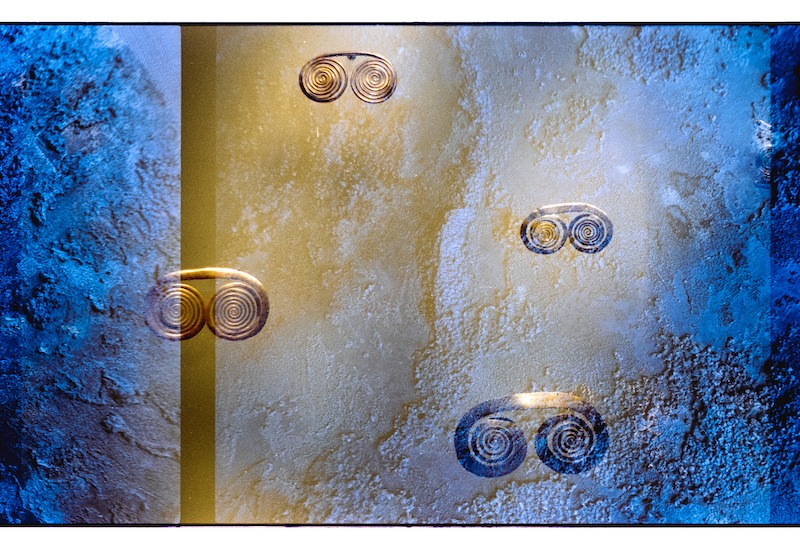

La gran producción orfebre, en Colombia y en Centroamérica se registró entre los años 400 d.C. y la colonización española. Colombia representa la región con mayor variedad en técnicas y estilos de orfebrería—la mayoría de las técnicas conocidas en Abya Yala fueron empleadas por los pueblos en Colombia. Esta diversidad se debe al hecho de que el territorio es un mosaico de nichos ecológicos, enmarcado por una diversidad geográfica y climática que condiciona diferentes adaptaciones humanas. Ciertos académicos consideran siete zonas de orfebrería mayores con un estilo definido: Tayrona, Sinú/Zenú, Quimbaya, Calima, Tolima y Nariño. Las zonas orfebres menores son: Tumaco, Cauca, Tierradentro y San Agustín.

Regiones orfebres de Colombia. Tomado de: Plazas de Nieto, C., & Falchetti, A. M. (1979). La orfebrería prehispánica de Colombia.

Los estudiosos de la orfebrería han denominado “horizontes” a las piezas en oro con una amplia distribución a lo largo de diferentes regiones orfebres. Un ejemplo de un horizonte es la nariguera en forma de media luna, piezas con un mismo patrón que aparecen con variaciones diferentes de la mayoría de las zonas de orfebrería colombianas. Uno de los horizontes más representativos son los Darién—figuras humanas esquematizadas—distribuidas en muchas regiones de Colombia, Panamá, Costa Rica y México. El fenómeno de los “horizontes” se puede explicar por las relaciones comerciales prehispánicas pero la existencia de un patrón básico compartido indica que los grupos que elaboraron las piezas debieron compartir rasgos culturales. Las modificaciones del patrón básico denotan los siglos de experimentación y técnica regional. Los horizontes indican las complejas interconexiones entre los grupos indígenas que habitan Abya Yala desde tiempos inmemoriales.

- Cronología de la orfebrería colombiana. Tomado de: Plazas de Nieto, C., & Falchetti, A. M. (1979). La orfebrería prehispánica de Colombia.

Bibliografía

Plazas de Nieto, C., & Falchetti, A. M. (1979). La orfebrería prehispánica de Colombia. Boletín Museo Del Oro, (3), 1-53. Recuperado a partir de https://publicaciones.banrepcultural.org/index.php/bmo/article/view/7354

Vargas Martínez, Gustavo. (1934). Americo Vespucio: El Primer Nombre. Recuperado a partir de https://www.banrepcultural.org/biblioteca-virtual/credencial-historia/numero-29/americo-vespucio-500-anos-del-descubrimiento-de-america